Humanitarian action today faces unprecedented structural challenges. The sector is grappling with drastically reduced funding, rising government hostility, misinformation and disinformation campaigns targeting aid work, and an alarming trend of institutional knowledge loss as experienced staff depart the aid sector. This turbulence risks a de-professionalisation of humanitarian action—with functions like security risk management among the most at risk of significant cuts based on current trends.

The converging challenges demand an urgent rethink of operational security solutions for aid work, including the relationship between humanitarian actors and private security providers (PSPs), and the risks and opportunities PSPs may bring as the sector adapts to massive structural shifts. The recently released third edition of the Good Practice Review 8 (GPR8) on humanitarian security risk management contains insights and cautions that can guide the sector as it navigates this uncertainty. In this article, GPR8’s Lead Editor Adelicia Fairbanks, discusses the application of the person-centred approach to guide interactions between the humanitarian sector and PSPs.

I. History of PSPs in the Humanitarian Sector

The relationship between humanitarian organisations and PSPs has been controversial and challenging. Early engagements in the 1990s and 2000s were decried as a “growth market” for security contractors prioritising profit over humanitarian values, with poorly designed, weakly overseen contracts. These were seen to create a variety of risks, including:

- Reputational risks: especially when PSPs play representative roles with the ability to influence how stakeholders and communities perceive the organisation.

- Operational risks: stemming from conflicts of interest, problematic PSP affiliations or an overreliance on generic security information.

- Security risks: Escalation of tensions and violent outcomes, especially when using armed protection.

The past two decades, however, saw significant progress in addressing these challenges. The Montreux Document and the International Code of Conduct for Private Security Providers, overseen by the International Code of Conduct Association (ICoCA), have set standards to promote responsible behaviour by private security companies. Additional guidance documents now exist for humanitarian organisations seeking to contract PSPs. These resources outline processes for due diligence, contracting PSPs that meet both organisational needs and international standards, and setting agreements with clear performance benchmarks, grievance mechanisms, induction on humanitarian principles, and strong monitoring and accountability measures.

At the end of the day, humanitarian actors cannot outsource their duty of care to PSPs, and this means that they must ensure that the companies they hire meet high standards and support their organisation’s values, principles and security policy and approaches.

II. New Challenges and the Latest Thinking in Humanitarian Security

There are two major areas that are particularly important for PSPs to understand if they are to be effective and credible actors supporting humanitarian operations going forward: the rise of mis/dis/malinformation threats and the sector’s shift toward a person-centred approach to security.

- Harmful Information

Humanitarian organisations are increasingly targeted by misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation campaigns (sometimes described collectively as ‘harmful information’). These can be spread for different purposes by various actors, including governments, armed groups, and the general public. They can create and perpetuate narratives that undermine trust, fuel hostility, and even incite violence against aid workers. PSPs engaged in guarding premises, managing access, or monitoring risks may be the first to encounter the real-world consequences of such narratives.

At its core, harmful information has shown the globalised nature of todays’ information landscape – what happens or is reported to have happened in one place can affect the security of individuals in a completely different location. For example, a video of a guard acting with hostility outside an NGO office can be recirculated online and reframed as ‘evidence’ of the NGO’s questionable reputation, fuelling hostility toward the organisation in other countries. Even the mere use or presence of PSPs can spark harmful narratives online.

PSPs need to be trained and sensitised not only to detect and report early signs of harmful information but also to understand the importance of communication strategies that reinforce their contracting organisation’s mandate, work and principles. They must also be well-placed to explain their relationship with the contracting humanitarian organisation. Similarly, humanitarian organisations must consider the impact that using PSPs may have on online discourses and incorporate these considerations in their risk assessments and contracting processes.

Conversely, PSPs can provide solutions for managing the risks of harmful information. PSPs that offer cybersecurity and media monitoring services are becoming increasingly relevant for humanitarian organisations that lack in-house capacity. One organisation, for example, has used a company to help them monitor mention of the organisation online and to flag when online threats may credibly turn into physical security risks.

2. Person-Centred Approach to Security

Perhaps the most significant conceptual shift in the humanitarian security risk management space, as outlined in detail in the third edition of the GPR8, is the ‘person-centred approach’. Traditionally, security planning has focused on location-based risks that fail to consider diversity in staff profiles. In contrast, this new approach shifts the question of ‘where is safe?’ to ‘who is safe?’ The aim is to move away from a homogenous approach that assumes all individuals face the same levels and nature of risk in a given context.

Security risks vary by the intersectional identities of individuals—gender, race, nationality, disability, sexual orientation, and more. For example, a female aid worker may face online harassment risks that her male colleagues do not; staff of certain nationalities may face profiling or xenophobia in particular locations. Marginalised groups may also face systemic and structural inequalities and challenges that not only affect the risks they face but also restrict their access to commensurate security support.

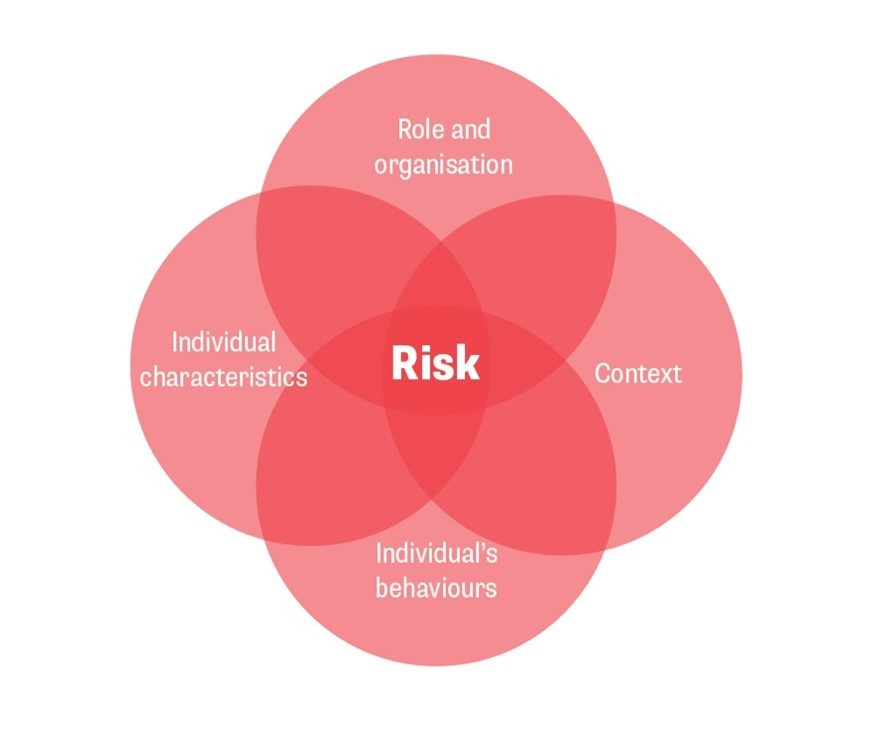

A person-centred approach essentially recognises the profile-specific risks that individuals face due to the intersection of individual characteristics and behaviour, organisational factors (like role and organisation), and the context in which staff are working (both in the physical and digital spheres) (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Person-centred approach to security (Source: Fairbanks, A. and Stoddard, A. (eds) (2025) Good Practice Review 8: Humanitarian Security Risk Management. Humanitarian Practice Network (HPN))

The aim of this approach is to tailor security measures as much as possible to identified specific needs and vulnerabilities. In practice this can mean ensuring risk assessments consider identity-based risks and that diverse perspectives are included in security risk management decision-making and implementation.

This approach, although relatively new in the humanitarian sector, is gaining traction and increasingly understood as a fundamental aspect of fulfilling organisational duty of care. This shift will increasingly affect contracted PSPs and is already becoming a key criterion for humanitarian organisations in service provider selection. PSPs can support this shift by, for example, ensuring their staff are trained to:

- Recognise how identity-based risks affect aid worker security.

- Include consideration of staff identities (as well as internal and online threats) in any services they provide, such as risk assessments, monitoring, and training.

For humanitarian organisations, this approach also means moving away from an overreliance on any PSP services, such as generic security information or training, that fail to account for diversity in risk.

III. The Relationship Moving Forward

It is still unclear how the current sectoral challenges are affecting the use of PSPs. On the one hand, reduced budgets may mean less money is available for PSP contracts, causing both sectors to shrink in tandem. On the other hand, humanitarian actors may feel pressured to outsource more security processes to PSPs when these may be cheaper than retaining in-house security staff.

The latter scenario carries the same risks that marked the early boom-market era. Namely, that with constrained budgets, private security contracts will go to the lowest bidders rather than the most qualified and principled providers. As experienced security professionals also leave the sector, there is an additional risk that much of the learning and good practice in responsible PSP contracting gets lost.

Interestingly, as humanitarian organisations face budget cuts and knowledge loss, a possible outcome may be that PSPs become custodians of critical humanitarian security risk management knowledge – such as good practice in risk analysis, security approaches, and crisis response. In the absence of another custodian, PSPs, if properly informed and aligned with humanitarian values and practices, could help conserve and apply this knowledge—ensuring continuity of professional humanitarian security practice at a time when it is most at risk.

IV. Conclusion

As the humanitarian sector undergoes massive changes, so will its relationship with PSPs, generating risks and opportunities. For humanitarian organisations, this is an opportunity to embed new thinking into how they work with PSPs, while ensuring that contracted companies consistently meet international standards and act as qualified, principled providers.

For PSPs, the challenge in the short-term is to remain informed and adapt to the latest challenges and approaches in humanitarian security risk management. In the long-term, it may be to position themselves as reliable, principled actors who can help conserve humanitarian security risk management knowledge in a fragile era for aid work.

ICoCA also remains an important actor in this new landscape, continuing to help bridge the gap between PSPs and humanitarian actors, ensuring standards are met and sharing learning and good practice on how to navigate existing and future challenges.

The views and opinions presented in this article belong solely to the authors and do not necessarily represent the stance of the International Code of Conduct Association (ICoCA).