The world’s vital shipping lanes face persistent, sophisticated attacks, yet the maritime industry clings to outdated, ineffective solutions while governments remain largely absent. To safeguard seafarers and security personnel, the industry must adopt cutting-edge technologies, balanced rules for the use of force (RUF), a reimagined approach to maritime security, and robust compliance architecture to responsibly mitigate these evolving threats.

I. The Escalating Threat

Seafarers and maritime security personnel alike face unprecedented dangers from hostile state and non-state actors wielding state-like capabilities. Merchant and fishing vessels are targeted by hostile forces with drones, missiles, water-borne IEDs (WBIEDs), sea mines, and limpet mines. They have fallen victim to unauthorized boarding by fast-boats and helicopters resulting in numerous injuries and deaths, major damage to infrastructure and cargo, unlawful seizure and arrest of vessels, crew and guards, hostage taking, and even sunk vessels.

Despite the increasing sophistication of these threats, the maritime security industry remains anchored to a model designed to prevent and deter simple acts of piracy and armed robbery. This approach—relying on small teams of lightly armed guards—is inadequate for today’s multidimensional threats which appear on and under the water, from the air, and in the electromagnetic spectrum.

II. The Limitations of the Current Model

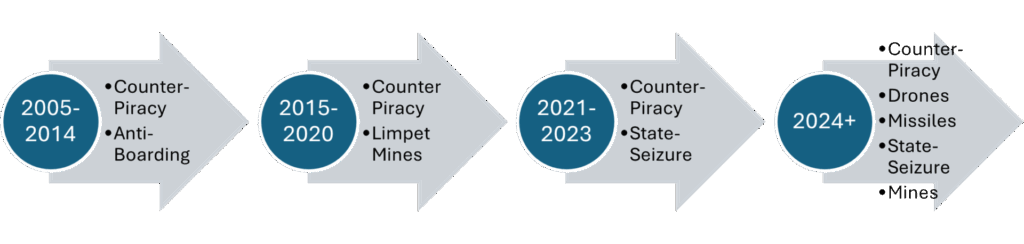

Over a decade ago, the private maritime security industry, as we know it today, emerged to combat Somali piracy; it was a private-sector response to scarce naval protection. Private Maritime Security Companies (PMSCs) deployed small teams of 3–4 privately contracted armed security personnel (PCASP) aboard client vessels, equipped with semi-automatic rifles and strict RUF, to deter pirate boardings. This model, supported by specialized insurance contracts and physical loss-prevention measures, effectively mitigated most piracy risks. But the threats have since evolved at a rapid pace.

At the same time, the industry’s primary clients—shipowners, charterers, and cargo owners—are private companies driven by cost sensitivity. Their relentless pressure to perpetually reduce prices for security services and extend payment terms, has eroded PMSC margins, forcing cost-cutting that compromises personnel training, equipment quality, and service standards, stunting the industry from an adequate and healthy evolution needed to counter the multiplication of threats.

Persistent client demands for lower prices have driven PMSCs into a race to the bottom, stifling innovation and leaving them ill-equipped with outdated tools, inadequate to counter contemporary threats. While combating maritime piracy involved defending against unsophisticated small-arms attacks from the water, today’s threats are far more complex, including aerial assaults from drones, missiles, and helicopters, as well as advanced waterside dangers like WBIEDs and subsurface weapons. For the Gulf of Aden and southern Red Sea, ship operators push for armed security teams at prices as low as $2,000 per transit, sometimes below cost—down from $50,000 in 2012—yet still expect PMSCs to counter modern multidimensional threats using the same outdated tools and tactics, or die trying.

III. A Mismatch in Expectations and Capabilities

This contradiction between clients’ demands for low-budget security and high expectations for sophisticated, multilayered defenses stands in sharp contrast to governmental efforts. Even billion-dollar warships, equipped with multimillion-dollar air-defense systems and supported by well-funded Coalition navies, frequently fail to counter these threats and have been notably absent during recent attacks. Yet, PMSCs are expected to maintain a daily presence on dozens of commercial vessels, neutralize advanced threats safely and reliably, and achieve this under zero-margin pricing, strained resources, frequent client payment delays, and significant legal exposure, all while somehow remaining profitable.

The highly publicized failure to prevent the 2024 WBIED attack on MV TUTOR, followed by the tragic 2025 attacks on the Greek-operated MV MAGIC SEAS and MV ETERNITY C, reignited industry debates over the inadequacy of current maritime security strategies. These incidents revealed a blunt reality: no government forces were available to defend the vessels or assist the stricken crews, leaving PMSCs to coordinate and execute rescue and recovery operations .

Now, Greece is reportedly dispatching a commercial salvage tug to the region, equipped with accommodations for “survivors” of future attacks. This is a grim acknowledgment of accepting the ongoing and unmitigated risks that mariners face in the Red Sea. Such a measure prepares for looming tragedies as if unavoidable, reflecting a lack of proactive initiatives to strengthen defenses and better protect crews and security personnel from the outset.

Compounding the issue, governments appear increasingly unable or unwilling to sustain their presence in this fight, signaling a potential withdrawal or abandonment from the region. This absence of state-backed defense creates a significant gap in the maritime security ecosystem, one that the private sector must now fill to protect itself. Though PMSCs recognize these challenges, they remain divided on critical issues: disclosures, effective mitigation strategies, and appropriate rules for the use of force (RUF), particularly given the risks of escalation when engaging hostile military and state-backed militia or so called proxy forces with advanced or state-like capabilities. Shipowners and operators must also introspect, reassess voyage planning, security expectations, and the value they assign, if any, to life-protecting services to ensure the safety of crews and guards.

The industry’s reliance on small teams armed with semi-automatic rifles— more or less the same tactics used for several hundred years to combat maritime piracy, with only slight enhancements – now sometimes promoted by PMSCs as willing to “fight to the death” against high-tech, unmanned threats, raises serious ethical questions. Is it reasonable to ask security personnel, often paid as little as $800 per month, to sacrifice their lives in an attempt to defeat a drone swarm or fight-off a hostile navy’s armed boarding team to protect containers of mass-market clothing, or grain, or cars, or oil, and its conveyance and crew? They signed an employment contract, not a death warrant. This approach to private maritime security risks treating human lives as expendable. This is a stark contrast to how the remaining Coalition military forces equip and protect their personnel in the same region today.

Would our military leaders send soldiers or sailors into this fight so ill-equipped? With such archaic strategies and systems? If not, why are we, as an industry, deploying our employees or contractors in such an unprepared manner? What tools and support should they be provided, or at least permitted, in order to effectively mitigate today’s multi-dimensional threats and meet the real demands of the market?

Do we even have at our disposal the right equipment to mitigate or defeat an attack by one drone or one WBIED? What about a group of ten drones? How about a simultaneous swarm of a dozen drones and a dozen WBIEDs which immobilize the vessel, immediately followed by a hostile helicopter and waterside combined boarding and seizure? Are you ready?

Better rise to the occasion. Because it’s already happening.

IV. A Call for Adoption of Best Available Technology

To address these threats and save personnel lives, the maritime security industry should adopt existing advanced technologies, including counter-drone systems, air-defense capabilities, electronic warfare (EW) tools and defenses against airborne and waterside threats. These systems could be deployed on civilian escort vessels operated by private security consortiums to protect civilian convoys in high-risk areas. Alternatively, modular systems could be temporarily mounted on merchant vessels during high-risk transits, with equipment deployed and recovered by offshore support vessels—a model already used for counter-piracy operations.

Just as the industry effectively shifted from land-based to offshore logistics, including use of vessel-based armories, years ago, another evolution is needed today- one that will see reimagined use of existing defensive technology and tactics borrowed from contemporary battlefields to counter sophisticated, unmanned and electromagnetic threats at sea.

To effectively counter modern threats, the private sector must forge partnerships to test, promote, approve, and deploy advanced kinetic solutions such as counter-UAV systems, air-defense, and waterside defense systems. Non-kinetic tools should also be integrated into the industry’s quiver and responsibly offered to ship-operators. These include drone-jamming and EW capabilities that can mask, modify, or obfuscate civilian vessels’ electromagnetic signatures to deceive adversary intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities in an attempt to mitigate targeting by hostile actors.

Transitioning from low-tech to high-tech solutions is a process that will require collaboration among PMSCs, technology vendors, regulators, and clients. At the same time, the process of proposing and deploying such systems raises concerns in certain circles, not only about cost, but also about compliance, international law, and the chance for misuse. The industry must balance innovation with accountability to ensure these tools are used responsibly and effectively.

V. The Need for Robust Compliance

Thus, the adoption of advanced technologies demands a corresponding evolution in governance and compliance to reassure all market participants and stakeholders. Following an earlier thought provoking ICoCA blog post regarding reconceptualizing security services that highlighted ICoCA’s Strategic Plan for 2024-2030 “calling for the integration into the Code of human rights standards relating to the incorporation of new technologies,” it is evident that the International Code of Conduct Association (ICoCA) is optimally positioned to spearhead this compliance initiative.

ICoCA is uniquely able to lead the development of balanced standards for deploying advanced security technologies at sea by bringing together PMSCs, technology vendors, ship operators, flag state authorities, and reputable civil society organizations. With its distinguished membership, including leading PMSCs aware of these challenges, and a motivated Board and Secretariat with the necessary expertise, ICoCA can address the regulatory gap, building on its commitment to integrate human rights standards into the use of new security technologies by the private sector in complex environments.

This multistakeholder framework must ensure the responsible use of powerful technologies by private entities, for the benefit of other private entities operating far from their regulating governments’ enforcement jurisdictions, minimize risks of diversion or misuse, and promote accountability while preserving innovation and protective capabilities. Such oversight will enhance safety and establish a trusted, commercially viable model for deploying high-tech security solutions at sea, fostering confidence among regulators, clients, and the public.

By aligning these stakeholders, ICoCA can facilitate the design of robust compliance architecture, ensuring the maritime security industry is equipped to meet future challenges ethically and effectively.

VI. Reimagining Private Maritime Security Services

Beyond technology and compliance, the private maritime security industry must reconceptualize its role. Private maritime security services in complex environments at sea are no longer just about preventing and deterring pirate boardings; but now require a holistic approach to counter multidimensional threats. This shift demands a new moral and operational philosophy—one that prioritizes duty of care obligations to seafarers and security personnel, underpinned by the adoption of advanced defensive technologies. Asking underpaid guards to combat sophisticated, unmanned threats with inadequate tools is neither sustainable nor ethical. Instead, the industry must invest in training, equip and protect personnel with fit-for-purpose equipment, and align pricing with the true cost of effective security.

The stakes are high. A simultaneous attack involving drone swarms, WBIEDs, and hostile boardings could overwhelm currently deployed defenses, endangering lives, destroying the sensitive marine environment, and disrupting global trade. The maritime industry cannot afford to remain reactive or complacent. We must expedite responsible adoption of effective technology to usher in a new era of sustainable growth.

VII. A Path Forward

The maritime security industry stands at the precipice. To protect seafarers, security personnel, and global commerce, as well as to remain relevant, it must embrace advanced technologies, establish robust compliance and standard-setting frameworks, and redefine its mission. ICoCA and its members can lead by fostering collaboration, developing innovative solutions, setting standards, and advocating for ethical conduct. Shipowners and operators must also step up, returning to value security as a critical investment rather than a cost to minimize.

The threats are real, and more serious than ever. We are facing them now. Industry must evolve or die. Uniting to reset the industry’s security architecture so that seafarers and security personnel are effectively equipped, professionally protected, reasonably remunerated, and ethically empowered to face the challenges of an exponentially evolving threat seascape is a necessity to sail safely into the future. It is not just a business imperative— it is a moral duty.

Adapted from original publication in The Maritime Executive

The views and opinions presented in this article belong solely to the author and do not necessarily represent the stance of the International Code of Conduct Association (ICoCA).